The McRae legend lives on

ASK a casual sports fan to name a rally driver, the chances are they wouldn’t come out with the sport’s most decorated star Sebastien Loeb, or his successor Sebastien Ogier.

The most likely scenario is that the name that would spring to mind would be of a Scotsman who became Britain’s first World Rally Champion in 1995 and sadly lost his life just over a decade ago in a helicopter accident.

Colin McRae was the man responsible for taking the niche discipline of rallying to the masses. He achieved that feat not only with his exciting, flat out, no-holds-barred approach to driving, but also as the face of the Colin McRae Rally PlayStation game phenomenon, which still exists today, albeit in a revamped form.

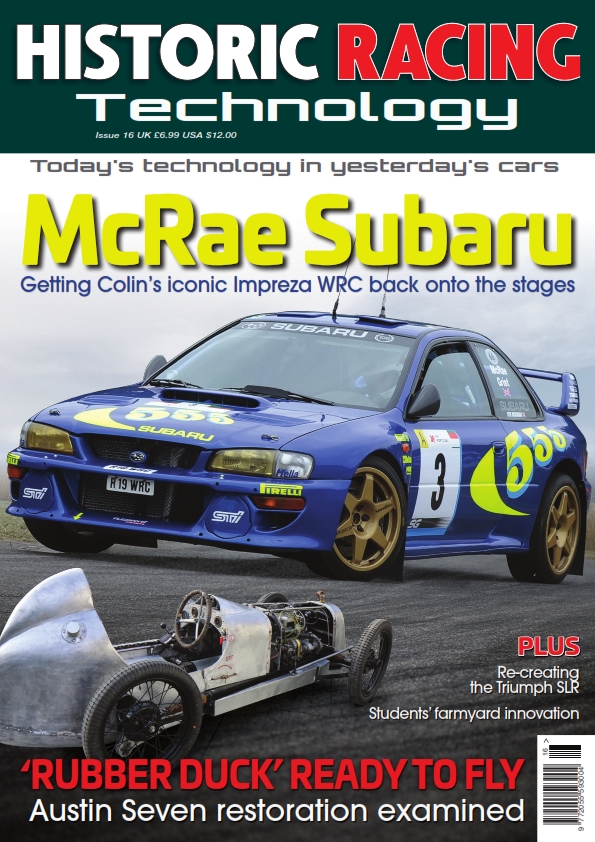

Despite driving Ford’s Focus at the turn of the millennium dressed in an iconic Martini livery, it’s the Subaru Imprezas of the mid-90s that the McRae name is most associated with. It’s that familiar blue and yellow livery that has been restored to adorn R19 WRC, the car with which McRae won Rally Portugal in 1998, his final year with the Prodrive-operated Japanese marque before switching to Ford.

R19 WRC (Impreza WRC chassis 019) made its WRC debut in the hands of Kenneth Eriksson on Rally Finland in 1997, the first year of the new WRC regulations taking over from the previous Group A rules. It was campaigned twice more by the Swede in Britain and Sweden, before McRae drove it to a Rally Portugal victory in March 1998, co-driven by Nicky Grist. The pair also achieved glory on Rally China, a round of the Asia Pacific series, in June of the same year.

PLAIN WHITE LIVERY

Subsequently, chassis 019 was used by Frenchman Frederic Dor in the WRC and French tarmac championship, until exchanging hands several times from the turn of the century.

When current owner Steve Rockingham acquired the machine, it was still in the plain white livery of privateer Dor. Having used it on a number of rallies in the same trim, engine problems on the Eifel Rallye meant a visit to Subaru preparation experts Autosportif Engineering in Bicester, based in the workshops of former Formula 1 team, March Engineering.

However, what was originally intended to be a relatively straightforward rebuild of the flat-four 2.0-litre engine, then turned into a full restoration. “The only thing that had really been changed when we got the car was that it had gone from left to right-hand drive,” says Rockingham. “We rallied it for few years and had so much fun with it, then we did the Eifel Rallye and it was breathing really heavily, with a puddle of oil on the floor. I took it to Howard [Dent, Autosportif Managing Director] to pull the engine out.”

The problem was diagnosed as a broken piston ring. But while the engine was being rebuilt, it was decided to convert the car back to left-hand drive. During that process, it was then decided that it was the perfect time to restore the car’s original colour too.

“We stripped it to a shell so it could be assessed at the bodyshop, then once it was blasted we had it back and decided what we wanted them to do,” says engineer Jon Hall. “They did all the welding repairs it needed, which was not a lot but there was some localised stuff, a floorpan and things for the left-hand drive parts. These always need some repairs because they’ve got floor guards on and when you take them off, there’s crud underneath that hasn’t been repaired, so there was a bit to do.”

Converting a car from right to left-hand drive, even on a machine that has had the opposite switch carried out previously, isn’t as straightforward as just moving the steering column and pedal box.

“There’s quite a bit to do because the wiper and wiper arms go on a different side too,” says Dent. “The brake lines are slightly different down the [transmission] tunnel because the pedal box has moved, and you obviously need to supply a new steering rack. You need a new dash top, although the dash panel is the same and the loom does swap over. There’s quite a lot of little bits and pieces that are wrong when you do that, so have to be modified. Then there were the carbon fibre parts for the heater and stuff that all needed changing. You’ve got to find the right bits or modify stuff to go back because when the conversion to right-hand drive was done, chances are the original stuff was taken out and launched.”

Never interned to be adapted, prior to 2003 Prodrive’s WRC Imprezas only left the firm’s Banbury workshops in LHD specification.

With the two-door bodyshell painted and the bulk of the hard restoration work done before the car could be reassembled, bolt-on components also having been restored off the car at Autosportif and subassembly completed, a stumbling block emerged. “It was nearly finished and we were stood in the workshop looking at it as a rolling shell,” says Hall. “It had a single roof vent, which was ’98 spec, but when McRae drove it in Portugal it still had the ’97 roof vents, so we asked Steve if we could change the roof. It was the last chance.” A roof skin was sourced from Japan and was immaculately fitted by the bodyshop.

“HORRIBLE EXPERIENCE”

“The car came back here with a brand new roof which we then had to cut two holes in to put the roof vents in, which is a horrible experience,” Hall recalls, referring to taking a jigsaw to the iconic machine’s lid to fit the original Prodrive vents. Another reason for the roof vent switch was in order to fit the two aerials that had been used on the car in Portugal ‘98.

The bonnet skin was also modified to fit larger period vents. Rather than just sticking them over holes in the panel, they were cut into the bonnet as in period by a fabrication expert, including adding the as-original aluminium lamp pod bobbins.

The stunning attention to detail is capped off by the Rally Portugal livery, fitted by the man who applied the same graphics to the works cars in period. “That is exactly how it finished Portugal,” says Dent. “Because there’s different stickers on the car on the finish ramp to when it started the rally, that’s how it finished. We deal with the guy, ‘Sticky Dave’, who put the liveries on in period.”

As part of the restoration process, the wiring harness was also rigorously checked by expert Robbie Durant, who removed any retro-fitted wires that had been added as temporary measures at some stage in the machine’s 20-year life. “It’s nice when you get in a car like this, turn everything on and it does what it’s meant to. A lot of them don’t, because to be honest not many people look after them properly,” says Hall.

In the same vein, all rose joins and bolts were also changed in critical areas like the suspension, to ensure reliability. Originally fitted with MacPherson Bilstein dampers as a Prodrive factory car, R19 WRC has been upgraded to more modern multi-way adjustable Reiger dampers (for high and low-speed bump and rebound, for instance) at each corner, attached to Prodrive’s uprights.

“Damper technology has moved on loads and the Reiger is a very, very good damper. They are better than the originals,” says Hall. The remote canister is located at the bottom of the strut. The change was implemented not only to improve the general driving characteristics, but also to make it competitive when it is used in events. “I still have the original dampers too, but the Reigers are so good. The car handles beautifully like it is. We could always put the period stuff back on, but all the time we use it, it’s kind of nice to have it working at its best,” says owner and driver Rockingham. The rear windows (made of thinner glass than standard, to save weight) are removable to enable adjustment to the rear dampers.

Although Rally Portugal was, and still is, a gravel event, the car currently sits in Tarmac specification, to suit what Rockingham most wants to use it for. As such, within the Pirelli-clad iconic gold 18” Speedline wheels sit Tarmac specification AP Racing six-pot water cooled brake callipers and 365 mm discs at the front. Four-pots would be used in gravel trim, the same as those found on the rear of this car, using a marginally thinner disc.

Aside from a recent refresh, the Impreza’s two-litre, four-cam, turbocharged (with regulation 34 mm restrictor) boxer engine remains much as it would have been in period, with a 92 mm bore and 75 mm stroke. The water injection and frontmounted intercooler are also as period to produce around 300 horsepower at 5,500 rpm and 471 Nm torque at 4,000 rpm. Such figures mean the Impreza is capable of reaching 60 mph from a standing start in around 3.9 seconds.

EGR VALVE

“In ‘97 they carried over the Group A turbo, but for the ‘98 car it was different. This is one of the areas [differentiating] a works car and a customer car, but Steve’s car is mechanically customer spec,” says Dent.

“The turbo is effectively Group N, but with a different compressor and

exhaust housing. There’s no anti-lag on a customer car, but it has an EGR [exhaust gas recirculation] valve which feeds compressed air from the turbo off-throttle back in under the turbo and keeps it spinning.

“It makes it a really driver-friendly car. This engine is still very similar to the last of the Group A engines [run in 1996], albeit with different cam pulleys, timing belt arrangement and a slightly different sump, but essentially it’s much the same.”

The six-speed H-pattern gearbox, fitted to the rear of the longitudinally mounted engine, is a fully active magnesium-cased Hewland unit. Its hydro-mechanical differentials give electronic-hydraulic control of the centre and front diffs, but with a non-active rear and a 50:50 torque split. The multi-plate carbon clutch is courtesy of AP Racing.

Although there were various options on Subaru WRC fuel tank capacities from Prodrive’s factory – a Safari Impreza having the biggest at 120 litres, and the smallest being 65 – space also had to be made underneath for water tanks.

This car has just one tank for the water injection system, located under where the back seats would usually be. The fuel tank sits in the boot, together with the spare wheel. Inside, the crew sit aboard a pair of bespoke Prodrive Sparco seats with Sabelt harnesses, looking at the Momo steering wheel just in front of the carbon fibre clad dashboard, housing an LCD driver display and enough fuses and switches to make it look more like an aircraft than a more modern racing car.

A period C-Giant trip meter was also sourced and fitted to the car, while a lifeline fire extinguisher system is installed behind the seats. Inside the rear quarter panels are tools and small parts for repairing the car at the roadside. In period, aluminium drinks bottles would also have been full of various fluids. Unlike in the Group A Impreza, the WRC version didn’t carry a spare turbocharger…

ABOVE

The technology harnessed within means the car is now arguably even better than it was when first built.

Like most factory-built competition machines, Prodrive’s WRC Impreza shares few components with its roadgoing cousin. “The thing is based on a road car, but there’s very, very little [left] isn’t there? On the engine there’s virtually nothing although the cam covers are the same,” says Dent. “The bodyshell is the same shape, but all of the mounting holes have got bobbins welded in bigger bolts; all the suspension’s fabricated [to have a wider track]. It’s like looking at a modern touring car, really. Even the front badge was different: it’s bolted to the bumper.”

“A MILLION BITS”

A 1997-98 Impreza bodyshell took around 300 hours to fabricate. Although the timescale of this restoration was rather less, it was still an involved process. “I don’t think I could say how long we spent on it,” says Dent. “It’s three days’ work to get a car into a million bits, then it’s probably three months to put it back together again. But, the biggest thing about that car is the initial look when you see it or open the door.

You know, when you walk into your bathroom and there’s a crack in the tile, it bugs you straight away. You can’t have that. It’s the initial look that makes you go, ‘Ah, it’s brilliant’.” There’s no sense of arrogance about the job done by Dent’s firm in that statement. Instead, it’s just the appreciation of the effort that has gone into making one of the most iconic rally cars ever built not only as good as it was when it was first winning in the hands of an all-time great 20 years ago, but now arguably even better.

“To own a McRae car is a bit of a privilege,” admits Rockingham. “Let’s face it, there’s not many cars that Colin actually won a round of the world championship in, so that’s quite nice. Like the early Group A cars, the early World Rally Cars are just fantastic, and it’s a wonderful thing to drive.

“Whatever bit of talent you’ve got, it flatters it; it does everything for you. It would be a crime not to use it. It’s so much fun I couldn’t just leave it sitting in the garage and look at it. Wherever you go with that car everyone just adores it, they all want to see it because it’s a Colin car. No matter where you are in Europe, he’s just a superstar and they all love anything to do with McRae, they go crazy for it.”