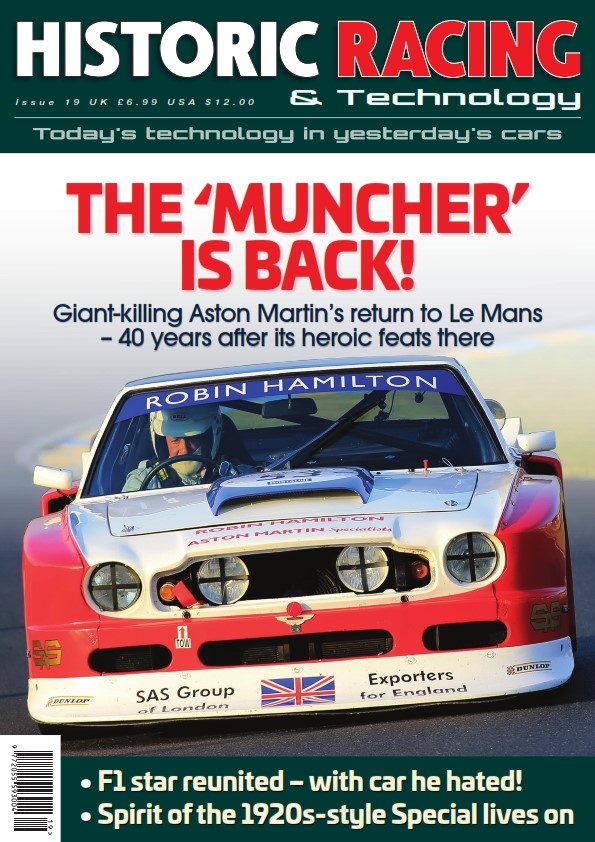

This time the ‘Muncher’ is eating up the miles – not the brakes

MOTORSPORT is full of great stories. One such tale was written in 1977 when Robin Hamilton, an official Aston Martin dealer and enthusiastic racer, decided that he was going to take on Le Mans. He did so with little more than words of encouragement and a session in MIRA’s wind tunnel from the then NewportPagnell-based carmaker, which was enduring one of its cyclical downturns.

Hamilton had David Jack (who now runs Aston Engineering) as one of the team of four that built the car for Le Mans. They started with a DBS V8 that they had already been using at club level, where it proved to be a decent competitor thanks to constant development work, but for Le Mans Hamilton planned something special. The car, decked out in a brutish body kit and making a ferocious noise, was given the chassis number RHAM1.

It was the first entrant to appear in the Le Mans paddock that year, an early start being necessary because Hamilton’s team needed time to finish building the car. Qualifying proved to be a fairly hectic affair, and after much ado the team scraped through in last place, which didn’t do anything to help shake the Forty perception in some of the paddock that the whole entry was a bit of a joke. Far from it, Hamilton had scrambled every resource he could to get the car to Le Mans and into the race, evidenced by the considerable list of contributors’ names on the bodywork.

PERSISTENCE PAYS OFF

In the 24 Hours itself Hamilton showed the determination that had got them into the race. Apart from eating through the first set of front brake discs and driving 17 hours on the cracked second set, which earned the car its nickname ‘The Muncher’, it all went astonishingly well. The big Aston, the heaviest car in the race by 275 kilos, placed third in the GTP class and 17th overall.

A week after proving the doubters wrong, The Muncher was back at Hamilton’s workshops, and was already being stripped down so the team could reuse its parts and modify and upgrade it with an eye on future attempts at the legendary French endurance test. Budget problems meant that the car wasn’t ready for the ’78 running, but the Aston made it back to the iconic race in 1979, this time with a twin-turbocharged iteration of the V8 blasting out more than 800 hp, and a heavily revised body kit. This monster was driven by Hamilton’s desire to beat Porsche 935s, but the lack of a proper intercooling system meant that its challenge was shortlived, bowing out of the 24 Hours early on thanks to a melted piston. It was this ‘79 car that was acquired by Paul Chase-Gardener in 2014, but it was the story of the ‘77 car which inspired him. “It just captured my imagination,” he recalls. “The whole thing about it being a dealer effort and the factory not being involved in racing because it couldn’t afford to at that particular time, it’s an inspiring tale.”

So when he took possession of the car, instead of working on restoring what was essentially a rolling museum piece, he was more enthusiastic about utilising the crates full of original components – including the engine from Le Mans in 1977, which came with the car – in a process that mirrors that of Hamilton 40 years earlier. His mission was to recreate the original and take it back to the Circuit de la Sarthe for the Le Mans Classic.

The first job was to get a donor car. Chase-Gardener managed to find a V8 club racer that had been recently racing in the Aston Martin Owners Club series. It had initially been built by Rex Woodgate, a former Aston Martin chief mechanic who then went to set up the eponymous Aston race and restoration business. This car had originally been given to Woodgate by Aston Martin as a development car for the Vantage, but it had since been heavily modified so was no longer in a form that preserved any historical significance. This made it perfect for the project.

FROM CLAY IT WAS CREATED

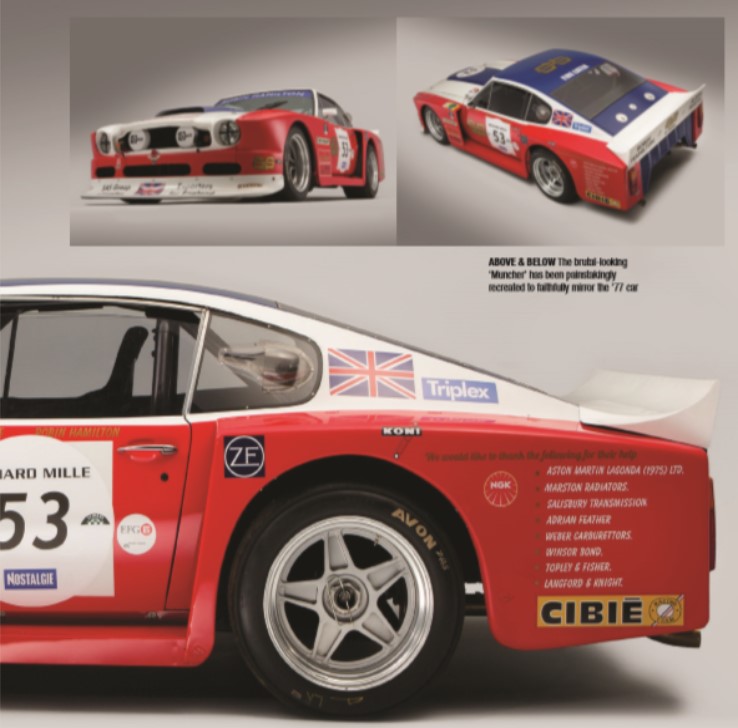

The donor car was then taken to Jaguar Specialist Leaping Cats because of great work they had done on one of ChaseGardener’s other cars. The final body extensions were made in fibreglass, the mould for which in period would be taken from bodywork shaped in aluminium. However, Leaping Cats recommended that a better way was to shape the bodywork in clay, a process that allowed the team to see the shape of The Muncher appear before their eyes.

“Leaping Cats do fantastic work, really, really first class, and their body maker essentially built the car out of clay. John Brown, the owner of Leaping Cats, was very enthusiastic and encouraging about the project from the start,” says Chase-Gardener.

The bodymaker, Nick Shakespeare from Bespoke Design, was constantly comparing the body he was recreating to pictures of the original as it raced at Le Mans, most of which were not in the public domain and were kindly supplied by Hamilton. Shakespeare was able to extrapolate from known dimensions in the pictures, and using precise laser measurements was able to build up a very accurate model of the car.

“He made it, and carefully shaped it, but then you could say, ‘I think that’s a little bit too wide’ and he’d just squash it and say, ‘Well how about that?’ It was a live moving thing. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

An aerodynamicist was also brought in to ensure that even documented aero work carried out in period was recreated. This also helped give ChaseGardener confidence in the car, for he was understandably “very keen that the car should not take off at 160 mph on the Mulsanne.”

Rounding out the authentic look of the recreation was the interior, which saw the original Muncher’s steering wheel mounted in front of a dashboard that had again been specially made with the help of photographs from the 1977 car to recreate the one that enclosed Hamilton for that endurance test. The level of detail is remarkable, to the point that as far as Hamilton can remember, the same roll of Dymo labelling tape was used to label the new dashboard as the one he originally used all those years ago.

With the body perfected, it was then time to start fitting out the car. One of the areas that required urgent attention was the wheels, hubs and tyres. In period it ran Dunlop crossplies, but they aren’t available now. Nor are modern tyres in the size required by the original wheels, so Paul and Alec Cooper of Coopersport, who was working on the car, set about finding a solution.

“We had to look at what was available to give us the sort of rolling diameter and width that we needed,” Cooper explains. “It turned out that some tyres that Avon were making were pretty much the right rolling diameter and pretty much the right width, but the profile of the tyre meant that they would sit on a different diameter rim.

“So then we had to make hubs and wheels to match the kind of tyre we could get. In the end it worked out well because the tyres we could get are used in the Porsche Supercup apparently, and Avon said that if you can use these then you can also have different compounds, wets, intermediates and different dry compounds, so it was a smart choice for racing.”

The brakes were another area that needed major attention. When Chase-Gardener first campaigned it at Le Mans in 2016, because of the short amount of time that had been available to get the car ready it had to remain on the “modern” club racing set up using open back six-piston callipers and large diameter discs. The rear brakes were still in standard road car form.

In period Hamilton enlisted the help of AP Racing to come up with a suitable system to stop the car. At the time it was developing a system for the Broadspeed Jaguars, whose twin fist-type system could be adapted to the Aston with a few modifications.

As David Jack was involved with the original brakes, it was just a matter of approaching AP again to obtain the original fist-type callipers, which, due to the demands of historic racing, have been remanufactured. A suitable size with matching discs was identified along with a slightly smaller version for the rear inboard brakes. It was then a matter of Aston Engineering designing and manufacturing suitable disc bells and calliper mounting brackets. It also added better brake cooling ducts than in period.

You can find the full story in Issue 19 of Historic Racing Technology. Find it here.